Some excerpts of commonly held understandings of Orthodox Christian Icons What is an icon ? The word “icon” means “image,” but since the early centuries of Christianity, the word “icon” is normally used to refer to images with a religious content, meaning and use. Most icons are two-dimensional; mosaics, paintings, enamels, miniatures, but ancient three dimensional icons also exist. Many people assume an icon must be in a Byzantine or Russian style. Many icons are, but many are not; other Orthodox Christian cultures have their own traditional styles of art, and many icons exist painted in a Western style and humanistic meaning. It is not style that makes a painting an icon, it is subject, meaning and use.

An icon is always the representation of a religious subject, but not every representation of a religious subject is an icon. The militant atheism of the Communist regimes produced anti-Christian caricatures of religious themes; these are obviously not icons. Nor are sentimental or even erotic portraits of models or historical figures masquerading as images of the saints, and unfortunately such paintings are very common in Western Christian religious art. An icon is not simply the representation of a religious subject, it is a representation with a religious meaning, and if it is an Orthodox icon it must have an orthodox meaning.

It may seem surprising that an image can be unorthodox. But consider for a moment: an image represents something – or it misrepresents something, or perhaps it represents a mere fiction. An image can mislead and it can lie – or it can be inadequate. It is for this reason Orthodox tradition forbids certain kinds of religious image. The Synod in Trullo, for example, which was convened in 692 to complete the work of the Fifth and Sixth Oecumenical Councils, forbids the depiction of Christ as a lamb, despite this having been a common image in the past, and insists He be represented in His humanity. [Canon 82] The reason for this is clearly stated; the image is to lead us to remember “His life in the flesh, His Sufferings, His Saving Death, and the deliverance accomplished for the world.” The Council of Moscow of 1667 forbade representations of God the Father as a human being – it was the Son Who took on humanity, not the Father, and representations of the Father in human form is deeply misleading.

There exist heretical images. In Western Europe, for example, the Jansenists sometimes depicted the crucifix in such a way that the arms of the Crucified are upraised, so that His hands are near together, not widespread as in orthodox images; they meant their heretical image to teach that Jesus died for a chosen elect, the few, not for all humanity. A beautiful Saxon crucifix exists which shows the soul of Jesus being carried up to Heaven by angels – but this is heretical, the soul of Jesus descended into Hades at His death, to destroy the power of Death.

The icon must not only represent a religious subject in an orthodox way, it is to be an image for religious use. Religious paintings that reproduce traditional Orthodox icons absolutely faithfully can nonetheless be inappropriate, even gravely objectionable. Canon 73 of the Synod in Trullo, for example, strictly forbids the placing of images of the Life-giving Cross on the floor where it may be walked on; it attaches the penalty of excommunication to this offence. Equally, it would be offensive to use reproductions of icons as decoration for the walls of a night-club or a casino.

Icons are part of the Church’s preaching and part of the Church’s prayer. The true iconographer prepares for the work of icon-making with prayer, fasting and study. The Church must be able to own and worship the image the iconographer produces. The icon must be truth.

The production of icons is a mode of prayer; they come from prayer to be used in prayer and worship.

Icons have an important role in the decoration of church buildings, in the church’s worship and in personal devotion. They play several roles:

Icons teach: they represent sacred persons, sacred events, they show us the reality of the Divine Kingdom. They teach history, doctrine, morality and theology. They remind us what we are and what we should be. They show us the importance of matter and of material things. They show us the transfiguration of matter under the power of the Holy Spirit.

It is Orthodox Theological understanding that every atom of the wood, canvas, paints, colors from the ancient icons of 50 AD to the computer generated icons of today are the manifestation of the Uncreative Energy of the Triune Creative Principle, Holy Spirit of God.

Icons challenge: we see the saints, transfigured by God’s grace and by their own free response to Him. We are challenged to follow in their footsteps.

Icons witness: the icon of Christ witnesses to the Incarnation. The Divine logos came down into our humanity; He is human as we are human. Humans can be portrayed; portraying the incarnate Logos, Jesus Christ, we witness to His true humanity.

Icons sanctify: generations of Orthodox children have gone off on long journeys, gone to war, emigrated, with their parents blessing them with the family’s most cherished icon. The presence of an icon in a house blesses the house and claims it and all who live in it for Christ. The Torah commanded the Jews to place “the Commandments I shall give you this day” in their doorposts: for Christians, the Law was a teacher for the Jews from the days of Moses to those of the Messiah, and now it is over; we set up the holy icons to sanctify our houses and declare our adherence to Christ.

Icons unite: photographs, films, videos of people we love can make them seem very close. The icons can make us feel very close to Christ and the saints – and this feeling of closeness is no illusion, the saints are alive in Christ, and He dwells in the depths of our own being -if we let Him. The icon is a doorway to the awareness of presence and the love of Christ and His saints and angels. Christ dwells in us by His Energy, and the saints and angels are already present with us, through their love and their prayers; the icon reminds us, and makes us aware of that presence in us.

We worship icons. The Iconoclasts tried to abolish icons from the Church’s life, but failed. They accused the icon-worshippers of idolatry, and claimed the making and worship of images was forbidden in the Bible. The Church’s response is firm and clear; the making of images is permissible – even in the Old Testament, God Himself commanded the making of certain images (e.g. the Cherubim on the cover of the Ark, [Exod.25,19]) and if they are images of Christ and His saints, then they are to be treated with reverence and veneration. We do not adore images; adoration [latreia] is due to God alone, but we do venerate and reverence them. The saints, as deified human beings living in the Kingdom, are also worshipped, and with a higher kind of worship than are their images, but no saint, not even the Theotokos herself, is ever adored.

Icons allow us a glimpse of the Kingdom of God, a vision the Word of God in human form, of humanity deified in the saints, of matter transfigured by the power of the Spirit. Icons are windows onto aspects of reality we cannot normally see, and help us awake our spiritual senses so that we become more vividly aware of the Divine energies that suffuse and uphold all Creation.

Icons and Imagination

Orthodox tradition is deeply suspicious of any attempt to give the imagination an important role in the spiritual life. This can seem very odd and even unreasonably restrictive to Christians familiar with the Roman Catholic techniques of mental prayer and discursive meditation, which make detailed and systematic use of the imagination -e.g. to imagine specific events in the life of Christ, which then provides the object-matter for meditation. Orthodox spirituality avoids any such practice. We are expected to read the Gospel accounts of the events in the life of Christ, to study the Fathers’ commentaries on the Gospel texts, to think about them….but not to attempt to imagine them in prayer. Using the imagination in prayer can lead to error of the gravest kind, when our own imaginative creations replace the reality, and we can even end up praying to our own mental fantasies.

The central reason for avoiding exercise of the imagination in prayer is theological. God is present everywhere. Christ is present by His Holy Spirit in the depth of the being of every Christian living the reality of Baptism into the death of Christ. If we live our Baptism, sealed with the Seal of the Spirit, then the Risen Christ lives in us, by His Holy Spirit, and we live the Risen life in the Spirit. We do not need to imagine Christ as present: He is present: we need to remind ourselves of His presence.

Icons can be effective in recalling us to the presence of Christ – the icon can serve as a reminder that He truly is here. Each specific icon type carries its own message about Him. The Pantocrator reminds us that the Christ who is present here is the Almighty, the Creator and Sustainer of the Universe, the Upholder of All. The icon of Christ the Teacher reminds us that it is He who teaches, through the Gospels, the Church’s proclamation of the Good News, through prayer, if our spiritual senses are awake to hear Him, through the people we meet, the situations we face. The icon of the Panteleimon, the All-Merciful, reminds us that nothing we have done is beyond His forgiveness; the Christ Who is present to us offers forgiveness and transformation, if we will accept it. The icon of the Crucified reminds us of the unlimited love of the Son of God who assumes our human nature in order to let us share His divine nature. He has entered into our humanity in its fullness, into our joys and sufferings, even into degradation and death; there is no part of our life where Christ is not. The Anastasis reminds us that Christ has descended into death to free the whole of humanity from the entrapping power of death, from the fear of death and from the compulsion to sin.

The iconographer has a grave responsibility to ensure his or her icons are not simply works of imagination. The iconographer exercises an ecclesiastical ministry in making icons. The icon must emerge from the mind and spirit of the Christ Bearer, and must ensure that new icons truly represent the reality the Church knows, not some individual fantasy. Prayer, scriptural study, study of the Church’s iconographical tradition and of the doctrine and canons on icons are as important in preparing oneself to make icons as technical study of the artistic processes involved.

The above is adapted from: http://www.orthodoxa.org/GB/orthodoxy/

iconography/whatisaniconGB.htm with my additions in italics or bold.

Understanding Icons as a Teaching Tool

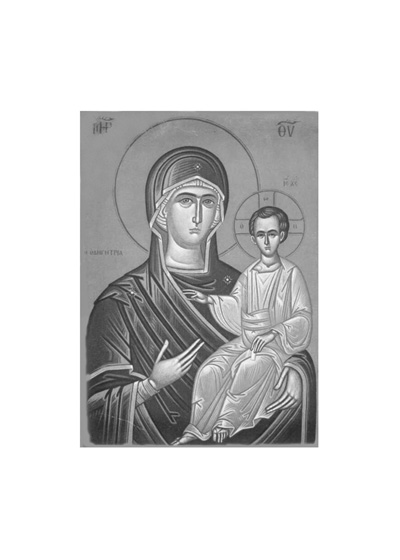

I present the following icon of Mary, the Theotokos, the Mother of God as an instructional tool for those that may not be familiar with the basics of iconography as a teaching tool.

#1 – The child in her arms is not a baby trying to do a man’s work. Here Christ is represented as a young adult male doing the work of a grown male as the Son of God.

#2 – In most icons when Christ is pictured face forward his right hand uses his fingers to teach a profound message. The index and middle fingers held together represent the two natures of humanity and divinity. The remaining three held together indicate the Holy Trinity, the Creative Principle, Father Son and Holy Spirit. In the left hand He is usually holding a scroll or book signifying that he is the Word of God, Teacher of Good (not the image of a carpenter or shepherd).

#3 – The narrow golden band of cloth draped over and down His right shoulder indicates that He is the son of a very important person, in this case God the Father. The right side of the body always means a revealing.

#4 – Mary’s right hand gestures in presentation of the Word of God, the Son of God, incarnated into Her human nature, our collective human nature in which we share in common.

#5 – Mary’s left arm and hand do not grasp or clutch the Christ figure but gently supports him; thereby not owning Him but supporting Him and His teaching.

#6 – The three golden stars on Mary’s head scarf and left and right shoulder indicate the trinity of God, which she bore (like a three star general). Not bad for a Jewish woman without a human husband to blame.

#7 – The physical features of the Holy Icons are different from normal physical characteristics as seen in western art as they do not represent resuscitated human beings, rather they represent the form as a spiritual idea in the Kingdom of Heaven not on Earth. Please take note of the following:

- Mouth – small and closed, almost petite, for in the Kingdom of Heaven there is no need for talking.

- Ears – large, for they hear the sounds of God’s Creation and Truth for all eternity.

- Eyes – are deep and mysterious, for they see all that was, is or will be.

- Fingers – elongated, a spiritual sign language for teaching.

Other characteristics not demonstrated in this Icon:

A scarf or cloth draped between two buildings or towers indicates being under the protection of the subject matter that the particular Icon portrays. The color of the cloth may play an important part as to the particular message; for example, white indicates God or purity and red indicates the movement of the Holy Spirit.

If a small skull exists at the base of the Crucified Christ it does not mean death, rather it represents mankind being in the hell of duality, but not extinct.

Final Thought

These Icons can be small for private use or traveling, or big, from floor to ceiling of a church. Even on the ceiling of a church like the Icon of Jesus the Christ-the Pantocreator-the word or voice from God in Heaven creating all that was, is or will be.

If we are called into being the image of God, then we are Icons.

Copyright © 2003-2009 Father Maximus Gregorios

All Rights Reserved